by Sarah A. Peterson-Camacho

Cordelia Brown Botkin was a woman of voracious and insatiable appetites: for sex, for sugar, for liquor, and gambling, and murder. And in time, she would become as well-known for her love of cheesecake photo shoots as she was for her love of the decadent dessert itself.

And for serving up a deadly dose of revenge by way of dark chocolate—and murder by mail…

While certainly not born with a silver spoon in her mouth, Cordelia Adelaide Brown came into this world still very much cushioned by privilege, in 1854—the middle of five daughters fathered by one Richard John Brown, Jr., who founded the little prairie town of Brownville, Nebraska, that very same year.

Surrounded by her sisters, she grew into a coquettish, voluptuous brunette in relative comfort, catching the eye of the splendiferously named Welcome A. Botkin when she was 17. Almost twice Cordelia’s age, the wealthy Armour meatpacking man swept the teen off her well-shod feet. Wed in early 1872, the girl would give birth to their only son Beverly before the year was out.

Saddled with a husband and a baby at barely 18, Mrs. Botkin nevertheless settled into the well-heeled life of a Kansas City society wife with ease, doting on little Beverly the way Welcome doted on her. And as the years passed, by the 1880s, the Botkins found themselves transplanted across the plains as Welcome’s line of work took them to the Central California city of Stockton—where the family of three continued to prosper both financially and socially.

But by the early 1890s—with two decades of marriage under her belt, and her only son grown and all but gone—Mrs. Cordelia Brown Botkin had grown bored. Still only in her thirties, the Stockton society matron now found herself saddled with a husband well over fifty, who would much rather stay in at night than go out on the town.

So “Cordelia, never a woman to stay tamely at home, visited her relatives frequently, and between times, lived by herself in San Francisco…There was a partial separation, but from time to time, [she] took steps to see that her husband could not divorce her for desertion—and often pulled out the classic stop, ‘I’ve given you the best years of my life, and you can’t cast me off now.’

“In return for the best years, she got an allowance which enabled her to have a very good time in the city [of San Francisco]” (Offord 122).

Fast-forward to a breezy September afternoon in 1895.

As the now-separated Mrs. Botkin and a friend lounged on a bench in Golden Gate Park, chatting idly while they took in the beautiful scenery, a dashing young gentleman stopped his bicycle in front of them. It had a flat tire, as Fate would have it.

Botkin’s lover John Preston Dunning, and his wife, murder victim Mary Elizabeth Dunning, from The San Francisco Examiner, dated Sunday, Sept. 4, 1898

As a foreign war correspondent for the Associated Press, the young journalist already had quite the reputation—having lived through shipwrecks, natural disasters, and bloodshed on foreign battlefields, spanning the entire globe—and had recently settled in San Francisco to head up the AP’s West Coast bureau.

Hailing from the state of Delaware, he had married a wealthy congressman’s daughter only a few years prior, sired a daughter—and then promptly abandoned them with his in-laws for more exciting pastures. Those far-flung writing assignments had afforded John P. Dunning the heady rush of adrenaline he so craved––and in Mrs. Cordelia Botkin, he found a kindred thrill-seeking spirit.

A pair of pin-up portraits Botkin posed for, from The San Francisco Examiner, dated Sunday, Sept. 4, 1898

Moving in together was the next swift step, with Cordelia and Dunning setting up house in adjoining apartments at 927 Geary Street. And before long, her hard-partying son Beverly joined them with his married mistress in a grossly inappropriate menage a quatre. Not that they cared what anybody thought.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the country, in Dover, Delaware, Dunning’s estranged wife Mary Elizabeth had more important concerns than her deadbeat husband and his married paramour. She had a child to raise by herself.

The youngest of five children born to the Honorable John B. Penington and his wife Rebecca, she could not have been more different from the woman her husband had taken up with. As dainty and modest as Cordelia was curvy and sensuous, the delicately pretty Elizabeth (as she was known) now resided with her young daughter, Mary Elizabeth, Jr., at the grand home of her parents in Dover.

The Penington clan was a close-knit bunch, by turns loving and lively, and the retired congressman and his wife often found themselves with a full house. For along with housing their youngest daughter and granddaughter, the couple often entertained their only grandson, Harry C. Penington, and his widowed mother, during the summer months.

And with their older daughter Ida Deane always dropping by with her husband Joshua and daughter Leila, the socializing never really ceased.

If anything could be said about Mrs. Mary Elizabeth Dunning, it was that she had a mighty wicked sweet tooth—and that she knew how to keep the peace. Her amicable relationship with her estranged husband might have seemed odd to most, but their genuine fondness for one another kept a steady stream of letters flowing between the two—much to Cordelia’s insane, jealous fury.

The Dunnings’ relative camaraderie became strained, however, in 1897, with “the receipt of several anonymous letters by Mrs. Dunning, at the Penington home in Delaware.

“She read the first letter, and wondered at it; showed it to her father; and sent a copy to Dunning…He passed it on to Cordelia, who loudly denied any responsibility…

“There were several more letters in the same hand, but after the first one, Mrs. Dunning asked her father not to give her any other that might arrive. There were later notes which, it was said, threatened her life if she should ever return to San Francisco, but these she never saw” (Offord 126-27).

Back on the West Coast, the good times appeared to be rolling less frequently as reality set it for John Preston Dunning. His extracurricular activities—namely, drinking and gambling himself into massive amounts of debt—had cost him his prestigious position as the Associated Press’ California agent. (Letting him go on the grounds of alleged embezzlement from the company, the AP had concluded it was cheaper just to fire him than to take him to court for the money he had already lost.)

Dunning now had to rely on the twice-monthly allowance his mistress received from her wealthy estranged husband in Stockton, as he found himself forced to quit his apartment and move into hers. The couple began to argue incessantly, even as the debauchery continued unabated.

“Liquor merchants in the neighborhood had difficulty in computing how many bottles of whiskey they had sold to Dunning and Beverly Botkin…at one party, there had been amateur athletics, in which [Beverly’s mistress] the sprightly Louise Seeley had repeatedly climbed on Beverly’s shoulders and jumped off, causing damage to the plaster in the flat below. The chandeliers were also feared for.

“At other times, the lively foursome would return exhausted from a long hard day at the Ingleside Race Track and, after reviving themselves with numerous ‘bracers,’ would lie side by side across the bed and tell ‘racy stories.’ When this palled, Cordelia would mount the chiffonier and dance, to applause and shrieks of laughter from her son and friends. The landlady would have asked the Botkins to leave, if she hadn’t been so badly in need of the room rent” (Offord 128).

Ironically, it would take the sinking of a ship—and the distant rumblings of a far-away war—to turn the tides for John P. Dunning, setting off a fateful chain of events that would end in a double murder.

On Tuesday, February 15, 1898, a massive explosion rocked the USS Maine, an American battleship stationed in Cuba’s Havana Harbor. Its sinking killed 266 of the 354 crewmen aboard.

In the tumultuous wake of the Maine’s fiery destruction, came the smoldering embers that would ignite the Spanish-American War. This would be big news in the weeks and months to come, the Associated Press ascertained, but who did they have on staff who would be foolhardy enough to dive headfirst into the action? And then live to report about it?

John Preston Dunning fairly leapt at the chance. This was his ticket out of the increasingly desperate situation he now found himself in, his final shot at any kind of redemption.

Cordelia “accompanied him across the Bay on March 9” by ferry, and “in the dim cavern of the Oakland Mole, Dunning boarded the transcontinental train. Cordelia rode with him for a few miles…and there, on the raised platform that echoed thunderously with train wheels, said goodbye…

“Some accounts say that at this last lovers’ parting, he told her he would never come back, that he meant to return to Elizabeth and the baby. According to Dunning’s own statement to reporters five months later, he wrote to her from New York, breaking the news from a safe distance.

“Dunning may not have been certain of his plans on that March evening, but he met Mrs. Dunning in Philadelphia within a few days, and if there had been any differences between husband and wife, they were settled before he left for Puerto Rico” (Offord 130-31).

Cordelia was beyond devastated. Her lover had dismissed her like a naughty child, and then literally sailed away, back to his real family—and to the very heart of another far-off war, chasing that ever-elusive adrenaline rush, which may have been the real love of his life. Not her.

So she simultaneously pined and plotted her long-distance revenge.

By the summer of 1898, the future looked bright for the Dunnings and their six-year-old daughter Mary. Though John was overseas covering the Spanish-American War, the little family had every expectation of being reunited at the foreign conflict’s conclusion.

On the evening of Tuesday, August 9, 1898, the senior Peningtons once again accommodated a packed house in Dover, Delaware: grandson Harry Penington, 15; oldest daughter Ida Deane; her husband Joshua; and their daughter (the Peningtons’ granddaughter) Leila, 14; and Elizabeth and Mary Dunning, of course.

Summer evenings found the ladies lounging on the front porch after supper, catching up on local gossip and watching the sun set. That second Tuesday in August proved to be no different. Like clockwork, about six ’o clock, Harry strode down to the Dover post office to retrieve the Peningtons’ mail. Only this time, there was a package for his Aunt Elizabeth, postmarked from San Francisco.

Given her well-known weakness for sweets, Elizabeth Dunning tore into the pink box of bonbons as soon as her nephew handed it over. “Mrs. Dunning opened the package in his presence,” reported The Morning News of Wilmington, Delaware, a month and a half later, “and it contained chocolate candies of different shapes and flavors, a lady’s handkerchief, and a note containing the following inscription: ‘With love to yourself and baby. Mrs. C.’”

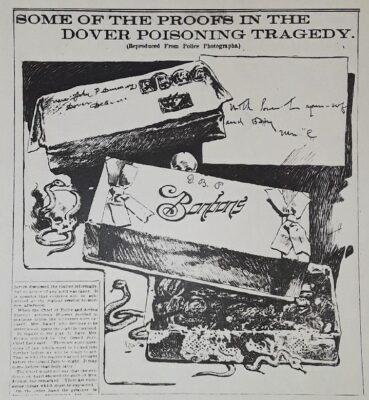

An illustration of the poisoned box of candy, from The San Francisco Chronicle, dated Wednesday, Aug. 31, 1898

Passing the box around to everyone else on the porch—her daughter Mary, sister Ida, niece Leila, nephew Harry, and two young neighbors, Misses Josephine Bateman and Ethel Millington—Elizabeth then offered a chocolate to her father John as he headed out the door on an errand, but he declined. Her older sister, however, indulged with her and they consumed at least three bonbons apiece.

Miss Bateman, for one, noticed something was off almost immediately. The young woman would later testify in a sworn affidavit, “…when she was eating the candy, she threw from her mouth—on three occasions—before the candy was entirely consumed, a foreign substance which resembled crystals…about half past eight p.m., she arrived at her home, and feeling something on her gums, she removed it with her finger, and found that it also resembled crystals…her gums and lips afterward became and were sore and irritated…

“…about 10 ‘o clock p.m., she felt a headache, and upon arising from her bed next morning, she suffered from a severe pain in her stomach…and was also troubled with her bowels—which continued all day of the tenth of August—until late in the day, she began to recover…her lips were sore for a week thereafter.”

Miss Millington and the three young cousins also suffered from headaches, nausea, and stomach pain in the hours after they had each consumed one piece of candy, but for Mrs. Dunning and Mrs. Deane, it would prove a different matter entirely.

By the time the Penington patriarch had returned from his errands around 9 ‘o clock, everyone else in the household had already retired for the evening, as witnessed by the dark and silent house. So, he did the same.

But early the next morning, John B. Penington was awakened by the sounds of his two daughters’ simultaneous retching. His wife Rebecca informed him of the situation, and by then, his son-in-law—Ida’s husband Joshua—had sent for the family physician.

But it would prove to be too little, too late. Ida Deane, 44, would be dead by the following evening, and Mary Elizabeth Dunning, 35, by the evening after that. In a matter of only two days, Mr. and Mrs. Penington had lost the remaining two of their five children, and the grieving couple would never entirely recover from this all-consuming loss.

On Monday, August 15, 1898, both sisters were laid to rest in the Old Presbyterian Cemetery in Dover—buried together in the same grave—to the collective wail of fifteen hundred weeping mourners. But it would take Elizabeth Dunning’s widower, enroute from Puerto Rico, ten days to reach New York by ship, and longer still to reach Delaware.

“It is said that Mrs. Dunning, just before her death, had her household goods packed, including her wedding presents, in order to move to New York,” The Delaware Gazette and State Journal revealed after the double funeral, “where she and her husband—who is reporting for the Associated Press—were going to start housekeeping, after the close of the war with Spain.”

The day after the sisters’ double funeral and subsequent burial, a coroner’s inquest was held to determine the cause and manner of death.

“The Levy Courtroom was crowded last night at the inquest called by Coroner Walls to investigate the tragic death of Mrs. Joshua D. Deane and Mrs. J.P. Dunning,” reported The Wilmington Evening Journal on Wednesday, August 17th, “having died in agony from eating candy on Tuesday night last…When Foreman Caleb S. Pennewill rapped for order, Dr. L.A.H. Bishop, who attended both women, was called and continued his testimony…

“There was a sensation that stirred the crowd almost into a tumult when Professor T.R. Wolf, state chemist, appeared with an analysis of the box of candy received by Mrs. Dunning through the mail from San Francisco.

“‘There is enough poison in that candy to kill many people,’ said the professor during his testimony, ‘and enough arsenic in the three bonbons I tested, to kill a horse.’”

The metaphorical dominoes began to fall almost immediately. After burying the last two of his five children, John B. Penington “examined the package—he now saw, too late, that it was postmarked San Francisco—and compare the writing with that of the anonymous letters which he had kept. They appeared identical…[John Preston] Dunning, who was still in Puerto Rico, was sent for. It took him ten days to reach New York, where he was met by his father-in-law with the letters. It was Dunning’s first sight of them. He said at once, ‘Cordelia.’

“In the meantime, the California newspapers had arrived at the same conclusion by tracking down the women well-known to have been intimate with Dunning. Cordelia was traced to Healdsburg” (Offord 135), where she was staying with a friend by the name of McClure.

The San Francisco Examiner promptly sent reporter Lizzie Livernash to infiltrate “the McClure home and gain Mrs. Botkin’s confidence” (Offord 135). This she did, and upon alerting Cordelia to the poisoned candy rumors flying about the country, Mrs. Botkin became hysterical, denying it all. At her friend Mrs. McClure’s suggestion, she at long last returned to her long-suffering husband in Stockton, in the company of new confidante Livernash.

“Cordelia, it was said, made an odd remark to her [Livernash]: ‘Oh, why didn’t I let the man die? Better to have let the man die and spared the mother to her child!’”

Indeed, Mrs. Cordelia Botkin’s time was up.

Now ensconced with a married mistress of his own, Welcome A. Botkin was anything but welcome to his straying wife, but he nonetheless sheltered her in her time of need—just not under his own roof.

Cordelia’s long-suffering husband put her up at the Windsor Hotel in downtown Stockton, where she was arrested by Detective E.L. Gibson of San Francisco—accompanied by Stockton’s Chief of Police Gall—on Tuesday, August 23, a full two weeks after the initial candy poisoning.

An illustration of Botkin’s husband escorting her to the jail car, from The Stockton Evening Mail, dated Wednesday, Aug. 24, 1898

But it was the beginning of the end for Cordelia Adelaide Brown Botkin. The authorities in Dover, Delaware, had officially handed the double murder case over to San Francisco Chief of Police Isaiah W. Lees—and with a veritable treasure trove of material witnesses, the puzzle pieces were being hammered into place like coffin nails in a closed casket.

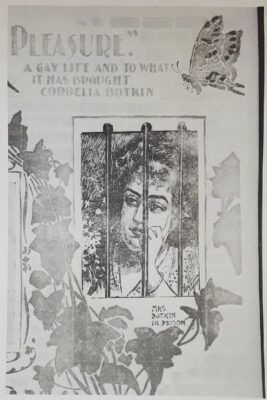

In the weeks leading up to the dual murder trial, the California press reveled in the sordid scandal of it all, publishing flattering portraits of the now rather portly Mrs. Botkin next to lascivious descriptions of the cheesecake photo shoots she was so fond of—reportedly in over 100 different poses!

An illustration of Cordelia Botkin behind bars, from The San Francisco Examiner, dated Sunday, Sept. 4, 1898

But by the dawning of 1899—the last year of the illustrious nineteenth century—the seeds of death had already been sown, and within a decade, all the major players in this whole saga would be dead.

And Mrs. Botkin would outlive them all.

Following his murderous wife’s February 1899 sentencing to life in prison, Welcome A. Botkin quietly obtained a divorce that March, with little fanfare and hardly any press. His ex-wife, however, would continue to make headlines.

Confined to the Branch County Jail in downtown San Francisco, Cordelia sowed her wild oats among her pick of the prison guards, garnering special privileges that included leaving the grounds of the jail.

“On a pleasant Sunday in March 1901, Judge [Carroll] Cook was on a Western Addition trolley car going out to visit his wife’s grave at the cemetery. As the car stopped near the Branch County Jail, he glanced out the window and could scarcely believe his eyes. Surely the woman who had just disembarked was that Mrs. Botkin—who he had sentenced two years before—to close confinement.

The stout figure disappeared in the direction of the jail, but before the judge could verify his theory, the car started and he was born onward…The sheriff’s staff swore up and down that ‘on the day in question, the noted prisoner was snugly locked in the jail.’ Cordelia, of course, also denied she’d been out.

“Investigation, however, disclosed that Cordelia had been using her charms on more than one of the jail staff…for in return for favors (unspecified), the jailers had provided her with a suite of rooms, special bedding and food, and now and then had given her an outing to keep her spirits up” (Offord 145).

Later that same month—March 1901—death came for the victims’ 74-year-old mother Rebecca Penington. She was buried next to all five of her deceased children in the Old Presbyterian Cemetery in Dover, Delaware—and would be joined in the grave by her husband, the Honorable John B. Penington only a little over a year later. The former Delaware congressman could go on no longer, passing away on the first of June 1902, at the age of 76.

But it would be the death of her ex-husband in 1904 that would finally bring Cordelia Brown Botkin to her knees in grief.

“Mrs. Cordelia Botkin—twice convicted of murder in the first degree—gazed yesterday, for the first time in her life, upon the face of a dead person,” The Berkeley Gazette divulged on Tuesday, May 3, 1904. “It was the face of her former husband, Welcome A. Botkin, who died last Saturday, and as she looked, she wept bitterly.”

Welcome had died a broke and broken man, having lost his fortune to her expensive legal defense. He had been living at the Royal House hotel in San Francisco’s Tenderloin District at the time of his passing—of congestive heart failure at the age of 65—with their newly married son Beverly holding vigil at his bedside.

“Yesterday by direction of Judge [Carroll] Cook, Deputy Sheriff Frank Johnson escorted Mrs. Botkin from the county jail to the undertaking room where the remains…lie awaiting burial. Some curious women of the neighborhood—attracted by the sight of the prisoner—begged the privilege of accompanying her to the inner room where the dead man lay, but the door was closed to all save Mrs. Botkin and her guardian.”

The following morning, “from a window in the prison, the convicted woman watched the funeral car pass,” revealed The San Francisco Examiner the next day. “She stood as one dazed, peering through the barred window, straining her eyes for a last view of the swiftly moving train. It passed, and the woman broke into hysterical weeping. She was led away by the matron, but in her room, she remained inconsolable…

“The matron stated that Mrs. Botkin seemed to feel that she had been the cause of her former husband’s death.”

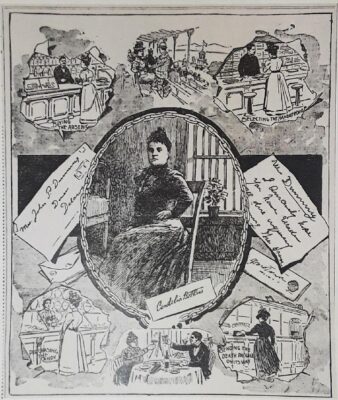

An illustration of Botkin enveloped by her crimes, from The San Francisco Call and Post, dated Tuesday, Sept. 6, 1898

“Her husband’s [Beverly’s] connection with the famous [murder] case was none too favorable,” noted The Stockton Evening Mail on Monday, February 20, 1905, “as he was accused of having been with his mother and others during the ‘Geary Street days’, when—according to testimony sworn to at the trial—it is said there had been all-night carousals.

“Later he [Beverly] came to Stockton, where he promised his mother, after her arrest, that he would lead a different life.”

One year to the day of his father’s death—Beverly Botkin himself died at the age of only 32. Even after he had reformed, his hard-partying past caught up with him in the end, his life snuffed out by an early heart attack.

“And although [he] refused [her] permission to attend the funeral of her divorced husband,” The Oroville Daily Register reported on Tuesday, May 2, 1905, “Superior Judge [Carroll] Cook has advised the Sheriff to allow her [Cordelia] to view the body of her son at the undertaking parlors in the city [San Francisco], and to follow his remains to the grave.”

Another year passed, and when a 7.9 magnitude earthquake leveled most of San Francisco on Wednesday, April 18, 1906—claiming over 3,000 lives—Mrs. Botkin was transferred to the women’s ward at San Quentin for the remainder of her days.

Exactly one year after the Great San Francisco Earthquake had shaken the Bay Area to its core, her former lover, John Preston Dunning, died of a brain tumor in a hospital in Philadelphia, a penniless alcoholic.

Having survived hurricanes, shipwrecks, and bloodshed on foreign battlefields, he ultimately succumbed to a cancer-eaten brain—his body weakened by liquor, neglect, poverty, and regret—at the age of only 44. He was mourned by his only daughter, Mary Elizabeth Dunning, Jr., now 15, who was being raised by his sister, another Mary Dunning.

He was also mourned by one Cordelia Adelaide Brown Botkin, who had loved and hated him enough to kill his wife and sister-in-law from over 3,000 miles away, though she herself would never admit just how much she had let her obsession with him destroy her life and those of everyone else around her.

Then death came for Cordelia herself.

“Mrs. Cordelia Botkin—central figure in one of the most noted murder trials in the country—died in San Quentin penitentiary at 9:30 ’o clock last night,” The San Francisco Call and Post summed up on Tuesday, March 8, 1910, “having been in prison for 12 years.

“In her death, there was written the last chapter of a story of love, intrigue, and murder, which electrified the entire United States…She died broken in health and spirits—a pitiable wreck of the dashing woman who, a dozen years ago, was the sensation of a continent.

“Since her imprisonment, all the important characters in the old tragedy have passed away. The man for whom she committed the murders is dead; her son Beverly, who fought for her, is dead; all the members of her family—saving her sister, Mrs. Dora Brown, and her aged mother—are dead…She realized that her last days were drawing to a close, and she hoped that at the last, she might be with her mother and sister in her old home in Healdsburg, but this was denied her.

“Her sister was with her when she died,” concluded the Call and Post. “Today the body of the murderess will be taken to her mother’s home.”

Cordelia Botkin’s cause of death was listed as: “softening of the brain, due to melancholy.” For at 56 years old, she had now reaped what she had long sowed…namely, death.

Works Cited

“Death from Candy.” The Morning New (Wilmington, Delaware), Friday, August 12, 1898, p. 1.

“Arsenic Caused Death.” The Evening Journal (Wilmington, Delaware), Wednesday, August 17, 1898, p. 1.

“Dover’s Day of Mourning.” The Delaware Gazette and State Journal, Thursday, August 18, 1898, p. 7.

“After Mrs. Botkin.” The Morning News (Wilmington, Delaware), Saturday, September 24, 1898, p. 1.

“Mrs. Rebecca A. Penington Dead.” The Sun (Wilmington, Delaware), Thursday, March 21, 1901, p. 4.

“John B. Penington Dead.” The Daily Republican (Wilmington, Delaware), Monday, June 2, 1902, p. 2.

“Mrs. Botkin in Tears.” The Berkeley Gazette, Tuesday, May 3, 1904, p. 5.

“Watches Funeral Train from Behind Jail Bars.” The San Francisco Examiner, Wednesday, May 4, 1904, p. 8.

“Mrs. Beverly Botkin Dead.” The Stockton Evening Mail, Monday, February 20, 1905, p 5.

“May Attend Son’s Funeral.” The Oroville Daily Register, Tuesday, May 2, 1905, p. 1.

“Beverly Botkin Dead Following His Father.” The Stockton Evening and Sunday Record, Tuesday, May 2, 1905, p. 8.

“Was a Noted Journalist.” The Fresno Morning Republican, Thursday, April 18, 1907, p. 8.

“Cordelia Botkin, Poisoner, is Dead.” The San Francisco Call and Post, Tuesday, March 8, 1910, p. 1.

Duke, Thomas Samuel. Celebrated Criminal Cases of America. San Francisco, California: The James H. Barry Company, 1910.

Offord, Lenore Glen. “The Gifts of Cordelia: The Case of Cordelia Botkin, 1898.” San Francisco Murders (Jackson, Joseph Henry, ed.). New York, New York: Duell, Sloan, and Pearce, 1947. Pp. 121-147.

Dowd, Katie. “Murder by Mail: The Story of San Francisco’s Most Infamous Female Poisoner.” SFGate, Monday, October 10, 2016. https://www.sfgate.com/bayarea/article/san-francisco-murder-poison-cordelia-botkin-9880884.php/

Duffy, Jim. “Flirtation to Fury: The Chocolate Candy Murders.” Secrets of the Eastern Shore, Friday, January 27, 2023. https://www.secretsoftheeasternshore.com/chocolate-candy-murders/

Mitchell, Robbie. “Bad Candy: Cordelia Botkin and the Chocolate Box Murders.” Historic Mysteries, Monday, October 2, 2023. https://www.historicmysteries.com/history/cordelia-botkin/36807/

Morrow, Jason Lucky. “Candy from a Stranger: The Cordelia Botkin Case of 1898.” Historical Crime Detective, undated. https://www.historicalcrimedetective.com/candy-from-a-stranger-the-cordelia-botkin-case-of-1898/

Dockery, Alfred. “Death by Chocolate.” Lessons from History (Medium), Monday, February 12, 2024. https://lessons-from-history/death-by-chocolate-ab1f379e705c/

www.findagrave.com

www.wikipedia.com

All photos provided by the author unless otherwise stated.

Check out other mystery articles, reviews, book giveaways & mystery short stories in our mystery section. And join our mystery Facebook group to keep up with everything mystery we post, and have a chance at some extra giveaways. Also listen to our new mystery podcast where mystery short stories and first chapters are read by actors! They are also available on Apple Podcasts, Google Play, and Spotify.

0 Comments