by Sarah A. Peterson-Camacho

Read Part 1 here.

Revenge is sweet, they say. That it is best served cold. And for no one was it sweeter—or colder—than it was for Josephine Melfi Trino Nocito the day she put a bullet in the head of her husband’s killer.

Rest in peace, indeed…

Friday, June 1, 1928, Fresno, California

From the moment bootlegging killer Antonio “Tony” Chiodo was acquitted of the ambush murder of one Santo Nocito, he was a dead man walking. Nocito’s grieving widow would make damn well sure of that.

As her husband’s grinning murderer shook the hand of his defense attorney in the Fresno County Courthouse, Mrs. Josephine Nocito seethed between her weeping daughters. She kept her dark eyes trained on the loudly ticking courtroom clock as trial-watchers filed out of the stuffy courthouse; the short, buxom Italian mother of four—her silver-kissed black hair swept back in a matronly chignon—did not know exactly how … or when … or where she would take out Chiodo, but…

As fate would have it, the cold-blooded slayer of one Santo Nocito had approximately ten days left to live.

Monday, June 11, 1928

It was a fine day for a funeral on this balmy, green Monday in June, as Joseph Gambero—a married 42-year-old father of seven—was lowered into the ground at Calvary Cemetery in Fresno. Several hundred mourners gathered around the descending casket to pay their final respects to this highly esteemed member of Fresno’s Italian community.

“Vengeance claimed its own today,” The Fresno Bee announced later that same day, “when a white-faced Latin woman walked up to the slayer of her husband—while they were attending the burial services of a mutual friend—placed a revolver behind his ear, and shot him dead.

“Mrs. Josephine Nocito, aged 40, mother of four children and wife of Santo Nocito—who was slain … in a duel last January—shot and killed Tony Chiodo, her husband’s slayer… Both were attending the funeral of Joe Gambero, 42 … a mutual friend. The casket had just been lowered into the grave when the black-clad, comely widow walked up to the slayer of her husband and opened fire.

“Chiodo, a well-known police character—who was acquitted by a jury June 1 of killing [Santo] Nocito—took the bullet behind the right ear,” revealed the Bee. “He fell immediately, blood gushing from his wound …With the sound of the shot, they [the mourners] turned around—Mrs. Nocito and Chiodo having been standing to the rear of the main crowd—and saw Chiodo fall … and Mrs. Nocito walked away.”

Clutching the small, nickel-plated .32-caliber revolver in her equally small hands, Santo Nocito’s widow spun on her heel and contentedly meandered through the murmuring crowd of mourners, away from Chiodo’s slumping frame. The gun in her hand glittered like a beacon in the dappled, late morning sunlight.

Meanwhile, Josephine’s oldest son James, 21—who had accompanied his mother to the cemetery that morning—remained blessedly oblivious of the bloody funeral scene, as he struggled to find parking in Calvary’s crowded lot.

But mourner Louis DeManty would have no such luck. One of only two eyewitnesses to the shooting, he leapt across the grave to reach Tony Chiodo’s lifeless form. A former member of the Fresno Fire Department, he was already well-acquainted with life-or-death situations—and knew time was of the essence.

Still, DeManty paused for a moment to take in the damage: while the bullet’s entry point was barely noticeable behind Chiodo’s right ear, the physical trauma wrought by the leaden round was a different matter entirely.

Blooming wetly from a meaty bouquet of brain and splintered bone, blood saturated the left half of Tony Chiodo’s shattered face in syrupy crimson. A matching ruby gush flooded his mouth and nose, bathing the rest of his features in a bloody mask.

A gentle breeze rustled through the trees overhead as Josephine Nocito wandered down a shady path among the silent, hulking stones of Calvary Cemetery. Tossing the shiny revolver into some brush, she didn’t really know where she was headed—and she didn’t really care.

She had avenged the murder of her Santo, and her heart was at peace. Whatever came next didn’t really matter.

Antonio “Tony” Chiodo, 35, was pronounced dead on arrival at the city hospital, and his body was turned over to Fresno County Coroner J. Herman Kennedy for autopsy.

Josephine, meanwhile, was soon happened upon by family friends, the Traficans, who had attended the funeral and set out to find her after the shooting. “The law gave Chiodo his freedom, and I killed him,” she confided to them. “I want to give myself up to the law.”

The little widow hitched a ride with them downtown to police headquarters, where Daniel Trafican escorted her inside. And then Mrs. Josephine Nocito turned herself in.

“Captain of Detectives Jackson L. Broad interviewed Mrs. Nocito,” The Fresno Bee continued, “in a room separated by a thin wall from the room in which lay the dead body of the man she had slain.

“There were no tears, no excitement. Her oval face … showed a slight pallor, but a sweet smile brightened up her features as she talked. She was dressed in black, in mourning for her slain husband. A black hat surmounted a head of jet-black hair, lined slightly with tinges of gray.

“‘I killed him,’ she said. ‘He killed my husband. This was my chance. I will not tell a lie, like Tony did, to the law. The night he was freed (referring to the acquittal of Chiodo in connection with the slaying of her husband), he came to my house. He drove by a lot of times, blowing his automobile horn. He blew on a mouth organ…

“‘My daughters were afraid, and I was afraid. He threatened me … said he would cut my face—cut my throat and kill my children … I have been living in [a] different house since he was freed—one night, one friend’s house, the next night, another friend’s house. Every time on the go. Three days ago, I got a little revolver…

“‘Today we were at the funeral of Joe Gambero. I saw him there. This was my chance, and I walked up to him and shot him. I will not lie like Tony did; I will tell the truth to the law.’”

And with that, Josephine Nocito was through talking; she had given a full confession, and—as far as she was concerned—absolved of all her sins. Upon signing her statement, she rose from her seat to be escorted by Captain Broad from police headquarters, where she was met by Deputy Sheriff W.H. Collins and Chief of Police William G. Walker.

Outside the station, a sea of newspaper reporters and photographers waited patiently for a scoop and a shot. And Santo Nocito’s widow would not leave them disappointed. Clutching her black hat with both tiny hands, she posed with the three officers—Collins, Broad, and Walker towering above her—in front of the police station.

But instead of a somber affair befitting a murder confession, the press was greeted by a surprisingly jovial quartet (Broad even flashed a jaunty grin for the cameras as he posed beside the little murderer). Exchanging pleasantries with her captors, Josephine shook their hands as she thanked the officers for their condolences over the death of her Santo. She knew the trio quite well, after all, from the murder trial ending in Tony Chiodo’s acquittal.

Waving goodbye to Captain Broad, the little widow accompanied Collins and Walker down to their awaiting automobile—and found herself whisked away to the Fresno County Jail. Her oldest son James, having located his mother at last, followed in a separate vehicle.

My God, what a day it had been…

Tuesday, June 12, 1928

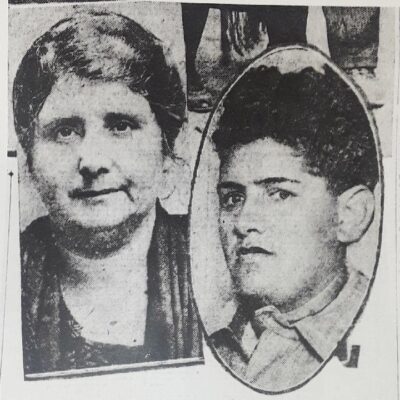

Shooter Josephine Nocito (left) and victim Tony Chiodo (right), from “The Fresno Morning Republican”, dated Tuesday, June 12, 1928

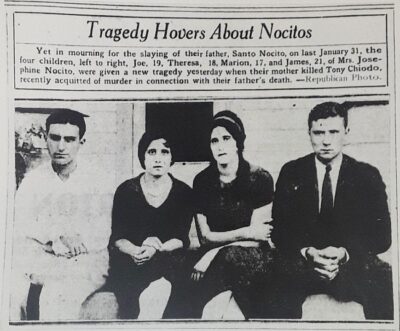

Joseph, 19, the only one in white, and James, 21, still in yesterday’s black funeral suit, bookended their devastated look-alike sisters: Theresa, just shy of 18, and Marion, almost 15, their dark eyes piercing the camera, their hair as black as their dresses. Their stepfather was gone, and now their mother was too. And here was a photographer from The Fresno Morning Republican, primed to capture their sorrow on celluloid.

Indeed, as The Fresno Bee was taking notes on Josephine’s first-hand confession, the Republican was over catching her offspring’s take. And while three of the siblings remained silent, oldest daughter Theresa spoke on their behalf.

“We were afraid of him [Tony Chiodo],” she told the Republican, “because the very night the jury freed him, he drove up in front of our house and blew his automobile horn until he had awakened us. Then he played on a harmonica. I got out of my bed and went to look out the window, but the machine was just driving away…”

“Soon after the slaying of the father [Santo Nocito],” divulged the Republican, “the family moved from what had been their home for years—a vine-covered ranch home at Marks and Muscat Avenues. They moved into Fresno and took up a small home [on D Street]. But since Chiodo’s release, they have lived in many places, afraid to stay home because of him.

“Foremost in their minds is a hope that the wheels of justice will move swiftly, and that their mother will be returned to them soon. To them, she is not a murderess. She is just their mother—and the avenger of their father’s death.”

Shooter Josephine Nocito with three police detectives the day of her capture, from “The Fresno Morning Republican,” dated Tuesday, June 12, 1928

Under the direction of Coroner Kennedy, Dr. George H. Sciaroni had performed Tony Chiodo’s autopsy, extracting a single leaden bullet embedded in the dead man’s mangled left cheek—which he believed to be of a .32-caliber—and promptly announced the death a homicide. But the revolver from whence it issued had yet to be found.

“Establishing a precedent in such cases,” The Fresno Morning Republican noted, “a coroner’s jury … returned a simple verdict of death from a ‘gunshot wound through the neck, inflicted by one Mrs. Josephine Nocito at Calvary Cemetery.’ Missing were the words ‘with homicidal intent,’ usually added by coroner’s juries in such inquest findings.”

Louis DeManty—one of only two eyewitnesses to the actual shooting—testified at the inquest that afternoon, alongside Captain Broad, Deputy Sheriff Collins, and Dr. Sciaroni. The good doctor “testified that the bullet was from a .32-caliber revolver—and had severed Chiodo’s jugular vein and lodged against his cheek.”

The shooter’s two sons and two daughters, from “The Fresno Morning Republican,” dated Tuesday, June 12, 1928

Santo Nocito’s widow, meanwhile, found herself appearing before City Justice Earle J. Church, who greeted her warmly before informing her of the murder charge that had been filed against her. Oh, and that she was to be held without bail.

Josephine, however, took this all in with a gracious nod. She may have had a sense of déjà vu at that moment, having gotten to know many of these same faces during Tony Chiodo’s trial for her husband’s murder mere weeks before. She held no grudge against this judge, nor the court clerks, the officers, or the attorneys.

But those Mrs. Nocito could not forgive were the twelve jurors who had acquitted her Santo’s cold-blooded slayer. They had believed Tony Chiodo’s lies of killing her husband in self-defense—despite the witnesses, despite the fact that Santo Nocito had been shot in the back of the head. All because her man had arrived to a scheduled duel armed to the teeth. Even though Chiodo had lain in wait, hiding like the true coward he was. And then fleeing town, like the true coward he was.

No, she would never forgive that jury. They could burn in hell with Tony Chiodo, for all she cared!

Wednesday, June 20, 1928

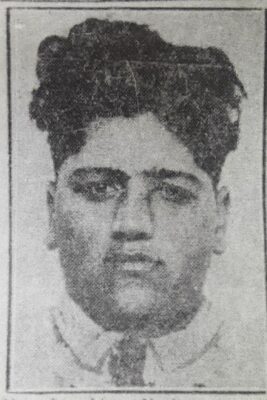

A mugshot of victim Tony Chiodo, taken after he killed his killer’s husband, from “The Fresno Bee,” dated Monday, June 11, 1928

Regardless, the graveside service—held in Mountain View Cemetery, a sepulchral neighbor to nearby Calvary—“was marked by a complete absence of the morbidly curious,” per The Fresno Morning Republican. Sponsoring the morose affair was Chiodo’s fraternal order, the Fresno Columbo Lodge of the Sons of Italy in America.

“Possibly half those present were members of the lodge,” noted the Republican, “while the rest represented intimate friends of Chiodo…” One notable presence was none other than Josephine Nocito’s estranged younger brother Frank Melfi—who had not only introduced his older sister to the love of her life, but he had also served nearly six years at San Quentin for the rape of his niece Theresa when she was only four years old.

“There were no church rites in connection with Chiodo’s funeral,” the newspaper continued, “he having been denied the last rites of the church—and also the privilege of resting in an ordained cemetery, a denial which brought forth hot criticism from many at the services, which occupied barely five minutes. The denial, it is understood, is the accepted procedure in the Roman Catholic Church, in cases of this kind.”

So not only had karma dealt Antonio Chiodo the same fate he had dealt Josephine’s husband Santo—namely, a bullet’s brain-scrambling trajectory from behind the right ear—but he had been spurned by his own faith in death. Denied both last rites and burial in consecrated ground, Chiodo was unceremoniously lowered into the ground without a priest’s final blessing, his sins ricocheting back at him threefold.

Tuesday, July 3, 1928

The preliminary hearing was a brief, but well-attended affair, the courtroom packed to the rafters with the morbidly curious—all those who had failed to show up at Tony Chiodo’s final send-off two weeks previous. Not only was every available seat taken, but “the crowd [was] overflowing into the fourth-floor lobby of the courthouse,” per The Fresno Bee.

City Justice Church presided over the hearing as Assistant D.A. Stewart called up just two witnesses for the state: Dr. Sciaroni, who had performed the autopsy, and Mrs. Rose Astone, the second of the two eyewitnesses to the funeral shooting. Josephine Nocito, meanwhile, sat in companionable silence between defense attorney Frank Curran and a jail matron.

Dr. Sciaroni—who had also performed the autopsy on Mrs. Nocito’s own husband five months prior—related the particulars of Tony Chiodo’s autopsy, while Mrs. Astone entertained the court with a dramatic reenactment of the graveside murder scene.

“I first saw Mrs. Nocito when she wormed her way in the crowd behind my brother-in-law,” Astone proclaimed through an interpreter. “I saw her lift up her arm, reach over the shoulder of my brother-in-law, and [I] heard the shot.

“I called out, ‘Luigi,’ because I was frightened, thinking at first that it was my relative who was shot.”

“Was the Mrs. Nocito who shot Chiodo the woman seated here as the defendant?” the assistant D.A. asked, gesturing toward Josephine, again all in black.

“Yes, it was,” Atone answered, pointing toward the serenely seated widow, who nodded with not quite a smile.

The defense attorney, for his part, “introduced no testimony,” the Bee noted, “and subjected the state witnesses to but a perfunctory cross examination.”

And that was that. If the spectators had been hoping for much in the way of drama and intrigue, Mrs. Astone’s theatrical interpretation of the alleged crime was as sensational as it got.

Monday, August 13, 1928

The summer of 1928 passed in a long, ugly-hot scrawl of scorching daytime temperatures and nights warm and sticky. But despite the sweltering confines of the Fresno County Jail, Mrs. Josephine Nocito kept her cool. All that mattered to her was that her late husband’s killer was dead, and her four children were safe. So let the law hang her if it dared!

Shooter Josephine Nocito, with a thumbnail photo of victim Tony Chiodo, from “The Oakland Tribune,” dated Wednesday, June 13, 1928

But finally, the first day of trial dawned in a blood-orange blaze, and the defendant, once again in her trademark mourning attire, entered the courtroom flanked by daughters Theresa and Marion. They joined their attorney Frank Curran at the defense table.

“It is expected to be one of the shortest criminal trials in the history of the county,” opined The Fresno Morning Republican, “because Mrs. Nocito freely admits having shot [Tony] Chiodo… Apparently both the prosecution and the defense—after admitting the slaying by the woman—are seeking a jury’s ruling on the simple question: ‘Was Mrs. Nocito justified in the slaying?’”

The Fresno Bee left it up to their readers to decide for themselves. “Was the old Mosaic law of an eye for an eye … applicable in the shooting of Tony Chiodo by Mrs. Josephine Nocito last June?” it asked its audience the day of the trial. “This question—while not one of law—will be decided by members of the jury.”

Presiding over the trial that Monday morning was Superior Judge Denver S. Church—the father of City Justice Earle J. Church—and assisting Assistant D.A. Richard K. Stewart for the prosecution was Deputy D.A. Claude Minard. And as for the jury, eleven men and one woman took their seats in awkward silence.

“Almost as swift as the dramatic tragedy which took the life of Tony Chiodo at a graveside,” the Republican began with a flourish, “the trial of Mrs. Josephine Nocito—charged with Chiodo’s murder—moved to a conclusion of simple evidence in an hour…

“The evidence was as simple as it was speedy in telling. Two witnesses to the shooting testified in almost as many words: ‘I saw it’—and Mrs. Nocito, matching their directness, testified: ‘I did it.’

“Unafraid and apparently eager to tell her story, Mrs. Nocito took the stand, at times to accuse the prosecution … of trying to confuse her. And once—under close questioning [by] Stewart as to her motives for the slaying—she said: ‘Why don’t you tell the jury, Mr. Stewart, what a bad man Chiodo was?’

“‘Yes, I know he was a bad man,’ Stewart said, ‘and the jury ought to have hung him.’”

And then, in a voice as musical as her hand gestures were animated, Santo Nocito’s widow told her story, her audience rapt. “When Chiodo … got out of jail June 1,” she said, “he threaten me. And he keep on. And on June 5 or 6, I got me a little gun and carry it in my purse … Then I go to the graveyard … I grabbed my little gun. I go close. I shoot.”

“How close?” Stewart asked.

“Oh, I don’t know,” Josephine replied, shrugging. “About a foot.” At that, the courtroom—again packed to the rafters with the morbidly curious—erupted with laughter. But the sharp rapping of the judge’s knuckles (the Superior Judge frequently eschewed the gavel) on the stand was warning enough to nix the giggles.

Josephine’s oldest daughter Theresa, newly 18, took the stand next, corroborated her mother’s story of Tony Chiodo’s taunts, intimidation, and threats—and of sleeping in a different house every night since his release. But she left it to her mother to disclose the reason for her stepfather’s murder.

“Before Chiodo murder my husband, he threatened to cut my face,” the widow Nocito revealed. “He said I told my daughter Theresa not to marry one friend of his. When I told my husband, he said, ‘I will speak to Tony Chiodo.’ [But] they have argument and then Chiodo, he kill my husband.

“That argument cause all the trouble. Chiodo stuck his nose into my family affairs. He wanted his friend to marry my daughter, and that caused all the trouble.”

The one-day trial wound down with the closing arguments. Deputy D.A. Claude Minard spoke for the prosecution, asking “that a verdict of guilty be returned by the jury as a ‘warning to the public that promiscuous killings in this community will not be countenanced,’” per The Fresno Bee.

“‘The killing of Tony Chiodo was an unlawful act,’ said Minard. ‘The only reason Mrs. Nocito killed Chiodo was to revenge her husband’s death. She pleads self-defense, and yet she admits—and the evidence proves—that she shot Chiodo in the back of the head.

“‘If you return a verdict of not guilty, you are telling the public that it can take the law into its own hands and kill promiscuously—and that a jury will exonerate the slaying.’”

Next up was defense attorney Frank Curran, whose impassioned plea to the jury resonated with sincere heartfelt emotion. He urged the jurors to free his client because of “‘a higher law than the laws of the State of California—the law of self-defense.

“‘When the people of Fresno heard that Mrs. Nocito had shot Chiodo—the murderer of her husband—a wave of approval of her act swept over this community,’ declared Curran. ‘As I stand here before you, I feel myself supported by unseen hands of red-blooded Americans who heartily approved of Mrs. Nocito’s act.

“‘Mrs. Nocito killed Tony Chiodo because she lived in daily fear of her life, from the time he was acquitted by a jury of the murder of her husband. And that acquittal was one of the most fearful miscarriages of justice in the history of Fresno County!’”

Curran’s powerful voice thundered off the walls of the packed courtroom, its rich timber ricocheting back onto a teary-eyed audience in vibrating echoes. Both judge and jury looked thoroughly moved––and so did the prosecution, for that matter…

Tuesday, August 14, 1928

Another Fresno scorcher dawned in a red-hot haze that singed the bleeding horizon like a cherry bomb. Today the verdict would be announced.

Emotions ran high as Josephine Nocito and her lookalike daughters descended upon the Fresno County Courthouse like the Three Fates, a glistening raven cloud of grief and ghosts. They took their seats with the defense as the morbidly curious absorbed every available space.

A fevered hush enveloped the murmuring crowd at the Superior Judge’s entrance. The rapping of his knuckles on the stand—his signature move—kickstarted the proceedings.

“Had there been a doubt as to what the jury would do in this case,” Republican reporter Ben F. Harrell wrote from his seat in the sea of spectators, “it began to be dispelled during the argument of both defense and prosecution counsel. The legal phase of the trial pointed more sharply toward a verdict of not guilty as Superior Judge Denver S. Church read the instructions to guide the 11 men and one woman to a decision.

“[He] instructed the body of 12 that before finding her guilty…they should carefully determine—because of threats [Tony] Chiodo made against her life, and the lives of her children—she was justified in shooting Chiodo.

“The simple, unconfused testimony of less than half a dozen witnesses—heard in an hour’s testimony Monday—had its effect on the argument, both of the defense and the prosecution.”

Deliberation was not long, and the silence was deafening as the mass of onlookers held their collective breath. The jury had returned.

“The crowd waited impatiently while the jury—having brought in a verdict—was sent back to correct the form the verdict was written on,” wrote Harrell. “When the jury returned, the news of its having reached a decision spread through the courthouse—and its return with a verdict in proper form—[it] was a struggle through a crowded court jammed to the doors.”

The jury foreman informed the judge that the body of 12 had come to a unanimous decision, having reached a verdict of not guilty.

“No sooner had the jury read the verdict than the calm of an August afternoon was shattered by a spontaneity of applause. Although the handclapping ceased with the authoritative battering of gavels…silent demonstration…continued as soundless tears poured down the cheeks of many of the women spectators.

“[But] not until the jury was dismissed did Mrs. Nocito rise from her seat. She stood trembling between the black-draped figures of two comely daughters, whose black eyes glistened with tears—and received the embraces of her family and friends.”

Santo Nocito’s little widow swore that she would never love another man for as long as she lived…but never say never.

Josephine Melfi Trino Nocito, 42, wed Francesco “Frank” Ferolito, 44, at the Fresno County Courthouse in the spring of 1930, her children in attendance. Frank, a widowed father of three, had lost his wife Antoinetta the previous year. Finally, the born romantic had found someone to grow old with.

Josephine’s daughters Theresa and Marion both suffered broken engagements—and broken hearts—in their late teens, but both eventually settled down and had children of their own—as did her sons James and Joseph.

And then, at long last, it was time to be with her Santo again. Josephine Melfi Trino Nocito Ferolito died two days before Christmas in 1962, at the age of 75: mother of four, grandmother of six, great-grandmother of four.

And finally—three and a half decades after she lost the love of her life to a barrage of bullets by the cowardly hand of one Antonio “Tony” Chiodo—Josepine was buried next to her Santo in Fresno’s Holy Cross Cemetery…where she remains to this very day.

Photos provided by author.

Works Cited

“Woman’s Bullet Seeks Out Victim in Funeral Crowd.” The Fresno Bee, Monday, June 11, 1928, p. 1.

“Widow Invokes Mosaic Law.” The Fresno Morning Republican, Tuesday, June 12, 1928, p. 9.

“Fatally Shot When Standing at Graveside.” The Fresno Morning Republican, Tuesday, June 12, 1928, p. 9.

“Home of Nocitos Wrecks by Two Tragedies; Only Children Remain.” The Fresno Morning Republican, Tuesday, June 12, 1928, p. 7.

“Avenging Widow May be Witness at Death Inquiry.” The Fresno Bee, Tuesday, June 12, 1928, p. 9.

“‘With Homicidal Intent’ Left Out of Verdict.” The Fresno Morning Republican, Wednesday, June 13, 1928, p. 9.

“Arraignment of Mrs. Nocito Expected Today.” The Fresno Bee, Wednesday, June 13, 1928, p. 9

“Mrs. Nocito Will Get Preliminary Hearing July 3.” The Fresno Morning Republican, Tuesday, June 19, 1928, p. 18.

“Chiodo Denied Church Rites; Slayer of Nocito Now Rests.” The Fresno Morning Republican, Thursday, June 21, 1928, p. 8.

“Mrs. Nocito Held to Face Charge of Chiodi Murder.” The Fresno Bee, Tuesday, July 3, 1928, p7

“Woman Slayer Faces Murder Charge Today.” The Fresno Morning Republican, Monday, Aug. 13, 1928, p. 5.

“Mrs. Nocito is Placed on Trial for Chiodi Death.” The Fresno Bee, Monday, Aug. 13, 1928, p. 7

“‘I Did It,’ Says Mrs. Nocito at Murder Trial.” The Fresno Morning Republican, Tuesday, Aug. 14, 1928, p. 9.

“Broken Love is Revealed Cause of Dual Slaying.” The Fresno Bee, Tuesday, Aug. 14, 1928, p9

Harrell, Ben F. “Woman Slayer of Tony Chiodo Freed by Jury.” The Fresno Morning Republican, Wednesday, Aug. 15, 1928, p. 7.

“Mrs. Nocito, Slayer of Man Who Killed Husband in Duel, to Wed Again.” The Fresno Morning Republican, Wednesday, March 19, 1930, p. 14.

Morrison, Scott. Murder in the Garden: Famous Crimes of Early Fresno County. Fresno, California: Craven Street Books, 2006. Pp. 122-131.

–www.findagrave.com –www.ancestry.com

0 Comments